Investigation reveals “organized crime” at one paper – how many more are undiscovered?

I know that I sound like a broken record on this subject, but for God’s sake, it’s been 3 years now since pretty much everybody in the digital ad industry acknowledged that there was a problem with the online ad ecosystem. To whit: advertisers are buying ads that NOBODY IS SEEING.Â

The botnet clickfraud problems are well-known. Here’s how that works:

- Online crooks pretend to be honest news sites, but really scrape content.

- The crooks then contract with ad exchanges who apparently ask no questions and do no real verification

- Crooks get ads placed on their pages.

- Crooks unleash swarms of bots on hacked computers around the world to click on these ads. Over and over again.

- Free money rolls in

- Advertisers wonder why their ad campaigns aren’t performing

The “newest” wrinkle in online clickfraud: pretend to be an honest & respected publisher

According to DigiDay, an internal investigation by the Financial Times, one of the biggest, most high-value publishers in the world, revealed that crooks were impersonating them and stealing about $1.3 million per month. (I actually shouldn’t say that this is a new wrinkle, because the tech nerds have been sounding the alarm over this practice for years, but it’s “new” in that the advertising industry seems to finally be taking it seriously. Ok, Ok. There’s a lot of room in that qualifier “seems.” But still. It’s something.)

On at least 10 different ad exchanges, there were people/organizations claiming to be the Financial Times, selling ads on the FT.com site. The problem is, the sites that these ads were appearing on had nothing to do with the FT.

“The scale of the fraud we found is jaw-dropping,†said Anthony Hitchings, the FT’s digital advertising operations director. “The industry continues to waste marketing budgets on what is essentially organized crime.â€

Let’s break this down just a little bit more, to make it explicit.

- Crooks don’t even bother building their own fake news site, but instead impersonate a “high value” publisher

- Crooks contract with ad-selling sites, pretending to be the New York Times, Wall St. Journal, Sports Illustrated – whatever site you can name that has a lot of respect and that has an audience that advertisers covetÂ

- Advertisers rush to buy ads

- Free money rolls in

The tech that is uncovering this clickfraud is part of an effort by the IAB to crack down on the fraud, because duh. (var “duh” = utter destruction of online advertising business model unless addressed)Â

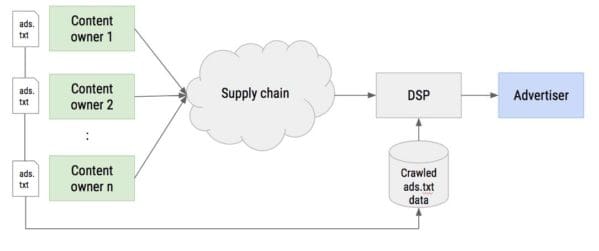

It’s called Ads.txt, and it’s basically a “whitelist” of authorized ad sellers. Which is kind of a brilliant move … but also a little troubling, for reasons that I’ll get to in a bit. They’ve got nifty little flowchart-esque graphics on the IAB site, which you can see below, that lay out how they think the flow of ad money should work:

This is their description of the problem, which again reads like a doctoral-level thesis on understatement:

The ads.txt project aims to prevent various types of counterfeit inventory across the ecosystem by improving transparency in the digital programmatic supply chain.

When a brand advertiser buys media programmatically, they rely on the fact that the URLs they purchase were legitimately sold by those publishers. The problem is, there is currently no way for a buyer to confirm who is responsible for selling those impressions across exchanges, and there are many different scenarios when the URL passed may not be an accurate representation of what the impression actually is or who is selling it. While every impression already includes publisher information from the OpenRTB protocol, including the page URL and Publisher.ID, there is no record or information confirming who owns each Publisher.ID, nor any way to confirm the validity of the information sent in the RTB bid request, leaving the door open to counterfeit inventory.

Fair enough. And their solution of creating a database where advertisers can check to see that what they are buying is what they are getting is a solid effort. However.

Here’s why I have some concerns: If you are going to flag a publisher as being suspect until such time as they get your “IAB Stamp Of Approval,” where does that leave the startups that we work with, who have not yet progressed to the level of, say, a Financial Times?

And what happens when a smaller publisher, who has been aggressively reporting on, say, the activities of a criminal gang that uses clickfraud as a cheap&easy revenue stream … is the target of a “smear” campaign by said criminals? One that then disqualifies said investigative journalists from participating in ad exchanges?